The US highway that helped break segregation

Along US Route 40, African ambassadors were regularly refused assistance at neighborhood foundations. In any case, their treatment set off a social liberties battle that prompted prohibiting isolation.

A

Adam Malick Sow had a migraine. He was a few hours into his outing from New York to Washington DC, and after his limousine crossed into the territory of Maryland, he requested that his driver track down a spot to stop.

A couple of miles later, the recently designated minister to the United States from the African country of Chad ventured into a burger joint along US Route 40 and requested some espresso.

The response on a mid year day in 1961 would change history.

The spouse of the coffee shop's proprietor wouldn't serve the negotiator since he was dark. "He seemed to be only a customary common [N-word] to me. I was unable to tell he was a diplomat," Mrs Leroy Merritt later told the public magazine Life. "I said 'There's no table help here'."

The affront ignited a global episode, making the first page of papers across Africa and Asia. Before long, negotiators from Niger, Cameroon and Togo detailed comparable encounters at Maryland cafés. Like others, they went on similar roadway from the United Nations in New York to their international safe havens in Washington. What's more, their treatment set off a little-recalled social liberties battle that made ready toward prohibiting isolation in the United States.

Today, not so much as a marker remembers the many exhibits that tracked with the street, and most explorers zoom by the area on Interstate 95, probably the most active roadway in the country. In any case, on the off chance that they look cautiously, they can observe hints of the astounding story of US Route 40, which matches Interstate 95 in northern Maryland.

Story go on beneath

A stone demonstrates the Mason-Dixon Line, the division between the US North and South (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

That is the means by which I wound up shoved aside weeds along a bustling four-path street searching for a half-covered stone showing the Mason-Dixon Line, the division between the US North and South. On its eastern edge, the line denotes the limit between the territories of Delaware and Maryland. Neighborhood history specialist Mike Dixon had shown me where to track down it. "That line had a ton of significance," he said.

Despite the fact that Delaware had a few isolated eateries at that point, in Maryland it was the standard. In 1961, when voyagers crossed into the state, they were dependent upon the laws of the South, where blacks were regularly refused assistance at eateries, stores and inns.

I fostered a profound scorn - one shared by a larger number of people - for Route 40

Stokely Carmichael, a trailblazer in the Black Power development, confronted ordinary embarrassments as an undergrad when he halted for dinners along the street. "I fostered a profound contempt - one shared by a larger number of people - for Route 40," he wrote in his book Ready for Revolution.

However, when the locale's dug in prejudice began to capture negotiators, US president John F Kennedy had to pay heed. The occurrences were a shame in the Cold War, compromising US worldwide impact. One State Department official imparted his disappointment to a columnist at that point: "Those damn limousines generally appear to run running on empty right when they get to Maryland."

Along US Route 40, African representatives were regularly refused assistance at nearby foundations (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

Also, Kennedy wasn't especially charitable about it by the same token. "Mightn't you at any point tell those African envoys not to drive on Route 40. It's an amazing street," he griped to a staff part. "I wouldn't consider driving from New York to Washington. Advise them to fly."

The issues were not really new. Almost 60 years before the ambassadors' objections, the territory of Maryland passed a regulation requiring isolation on open transportation. Dark train travelers had to move to a "shaded vehicle" when they showed up in Maryland. A couple of months after the fact, a dark regulation teacher wouldn't surrender his seat and was captured, prompting a legitimate case that at last upset aspect of the law. The court denied isolation for highway travelers whose excursion started beyond Maryland yet permitted it for the people who were going inside the state.

Today, a little block train station, simply off Route 40 in Elkton, Maryland, is utilized for stockpiling. Many Amtrak trains zoom by day to day, without a sign that for a period the town was a stop to sort travelers by race.

In the mid 1960s, the arranging was going on at cafes, cafés and inns. In the weeks after the occurrence with Ambassador Sow, the central government discreetly started to constrain Maryland restaurateurs to serve negotiators going through the area. Be that as it may, no sooner had a portion of the organizations consented to agree, once more, then the issue erupted.

Today, Elkton, Maryland's little block train station, simply off Route 40, is utilized for stockpiling (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

Three dark columnists from Maryland's Afro-American paper arranged an intricate act. Two spruced up in tailcoats and formal hats, and a third wore a robe and panther skin crown. They introduced themselves at Route 40 eateries, professing to be authorities from the non-existent East African nation of Goban. One, who called himself Orfa (Afro spelled in reverse), acted like the priest of money. In their ensuing article, the writers reported that they were served all things considered eateries as long as they imagined that they weren't American.

The article insulted quite a large number. "It would make you insane assuming that you contemplated it adequately long," said Charles Mason, a dark Baltimore occupant who was 21 at that point.

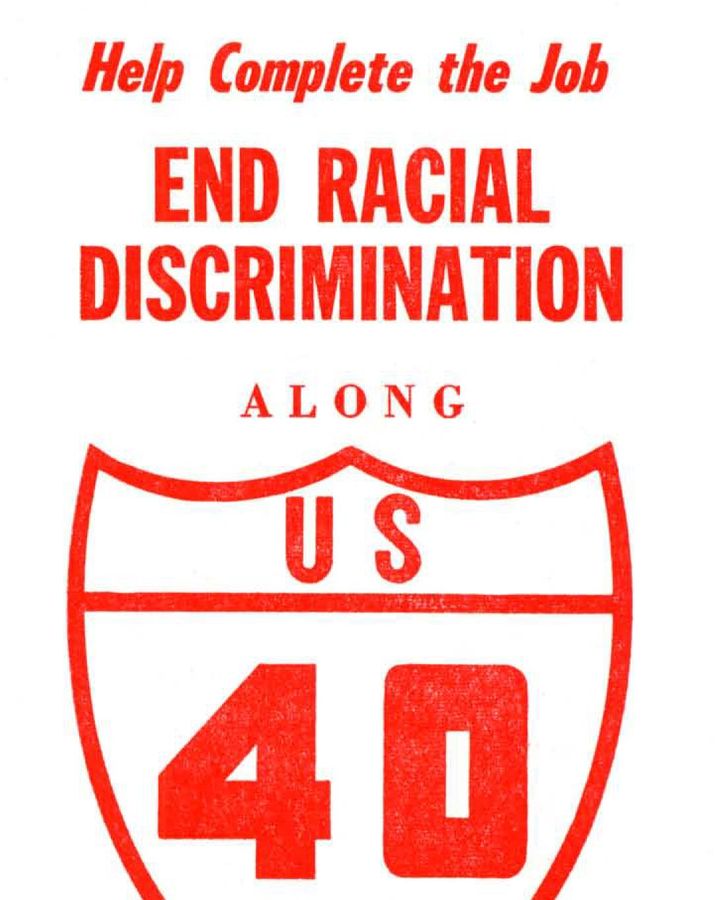

He worked with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a public bi-racial gathering dedicated to integration, arranging picket lines along Route 40. The gathering called the work Freedom Rides, a gesture to the development battling isolation on transports and in open convenience across the Deep South. Center disseminated a handout posting eateries that professed to serve all voyagers ones that actually were isolated. "Assist with finishing the task," it asked protestors. "End racial segregation along US 40."

Artisan, presently 82, joined exhibitions on ends of the week, dressing in formal attire, while ladies wore dresses. "We needed to show a decent picture." Often, they were welcomed by threatening groups.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) dispersed a leaflet posting cafés that endlessly were not isolated (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

"We were terrified. We all were terrified," he said. He recollects white individuals shouting and hollering and "needing to slam me in the head".

Bricklayer will be highlighted in a Black history display opening in May at the Maryland Center for History and Culture. Amy Nathan, a Maryland writer who expounds on the social equality development, said the acknowledgment is very much past due.

"These were individual endeavors by individuals who had recently had enough, and they saw things should have been changed," Nathan said. "They were simply strolling to and fro before a side of the road eatery, however it's memorable's great that what might appear to be a little exertion, when joined with different endeavors, may have a major outcome."

The majority of the organizations that confronted fights are a distant memory, supplanted by strip retail outlets, drive-thru eateries and gas stations. In any case, a couple remain.

At one, the Bar-H Chuck House in the Maryland town of North East, four demonstrators were captured when they wouldn't leave. After they were imprisoned, three organized a yearning strike, Dixon told me. The area sheriff sent the strikers to the state mental emergency clinic, saying the detainees must be crazy to decline food. Yet, in no less than 24 hours, they were once again at the lockup. "The state specialist said: 'They aren't insane, they're simply fighting for civil rights'," Dixon said.

Rayshad Beepath, from Trinidad and Tobago, and his significant other Marylena own Ray's Caribbean American Food (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

The cafe's presently called North East Family Restaurant and claimed by Ed Omar, initially from Alexandria, Egypt. He had never heard the story until I came by one morning. "I recently gained some new useful knowledge," he said. "I'm North African. Check me out. I'd be the first they'd kick out.

Server April Jones can't envision declining to serve somebody who was dark. "Are you not kidding?" she said. "It is insane. It's changed a ton."

I must Google this. It's something incredible to put on the divider

I had a comparable encounter under 20 miles not too far off at the previous Sportsmen Grill, which in 1961 confronted white picketers conveying signs with messages like: "How about we Have Dinner Together" and "We should End Racism in America Now."

Today, the eatery in Aberdeen works as Ray's Caribbean American Food. Proprietor Rayshad Beepath, a worker from Trinidad and Tobago, was astonished when I showed him an image of the dissent. "I had no clue, no sign" he said. "I must Google this. It's something incredible to put on the divider."

Today, the previous Sportsmen Grill in Aberdeen works as Ray's Caribbean American Food

The exhibitions made their difference. In 1963, Maryland passed a regulation restricting separation in inns, eateries and different facilities. "The fights excited the lead representative and the assembly. It was the first

August122

Great